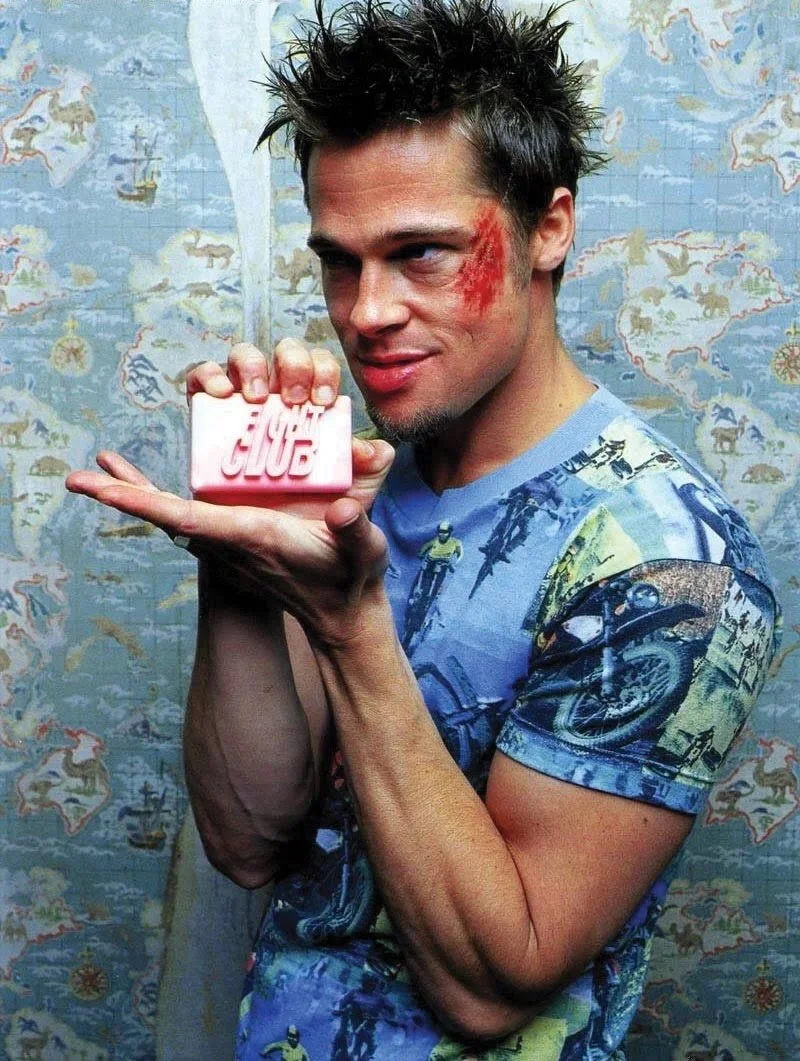

Tyler Durden is better at business than you

Serial entrepreneur and all-round headcase, Durden started Fight Club with nothing but an idea and a fuck ton of hustle.

No capital, no premises, no partners. No sales team, no dev department, no network infrastructure.

So, what can this maniac teach us about building a successful business?

Create something people want

This is called Product-Market Fit.

Durden identified and capitalised on an untapped societal need.

He offered dissatisfied men numbed by the monotony of their jobs and mundanity of their lives a way to escape the grind.

Self start

Durden started Fight Club in the parking lot of a sleazy bar and eventually wrangled a premises in the basement of that sleazy bar, rent free. There’s that fuck ton of hustle.

Before Fight Club, Durden founded a successful soap company

Inspire

This is a must for every leader. Durden did it with rousing manifestos:

“Man, I see in fight club the strongest and smartest men who’ve ever lived. I see all this potential, and I see it squandered. God damn it, an entire generation pumping gas, waiting tables; slaves with white collars. Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need. We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars. But we won’t. And we’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very, very pissed off.”

Take a bow, sir. But he also walked the walk.

By negotiating with Lou the landlord for an indefinite extension on his lease at a continuing rate zero dollars per month, he saved the business from losing its headquarters.

Expand aggressively

Not long after opening, Fight Club affiliates started popping up in cities across America.

Durden struck a corporate sponsorship deal with a major car company where he worked as a recall co-ordinator.

He scaled back his day to day role, staying on as a consultant, and devoted all his attention to his fledgling business.

To meet skyrocketing demand, Fight Club opened every night of the week.

Outline your operating framework

Durden laid out the mechanics of Fight Club with eight simple rules.

This standardised process meant he could expand quickly and easily later on.

He cleverly leveraged social currency by asking users to keep it a secret, which of course urged them to tell their friends, driving early growth.

He set out guidelines to govern each fight and by making newcomers get in the ring on their first visit, he had a solid way to convert trialists into new users.

Forget about getting your seven hours a night

When you start a new business, you have to sacrifice some sleep.

Durden went and knocked it on the head completely by becoming an insomniac.

Drive demand

In the same way an economy works, Durden kept demand for Fight Club high through scarcity, by initially making it available in only one place, on only one night a week.

He also lowered the barriers to adoption, making it free to all.

Adapt and evolve

Durden kept his operation nimble. Always iterative, always evolving. Member homework assignments went into beta testing and proved invaluable for building team morale. And soon Fight Club morphed into the anti-corporate, anti-materialist Project Mayhem.

With that came the move to a bigger premises on Paper St. And monetisation through member sign up fees.

Durden introduced a gruelling recruitment process and built extremely effective in-house production and execution teams.

Due to budget constraints, Mayhem concentrated on the generation of free media with guerrilla stunts that were picked up by local News broadcasts.

This helped elevate the organisation beyond dingy basement bust ups—if Fight Club existed to liberate individuals from their dead end lives, Project Mayhem existed to liberate society from capitalist culture & corporate greed.

Don’t let anything deter you

Do you think Durden let his Dissociative Identity Disorder stop him? Fuck no, it was the driving force behind his success.

And although he was probably a terrorist, Durden teaches us the value of a clear vision and inspires us to create not just a business, but a movement.

That’s where the real power is.

Maverick advertising

Lieutenant Pete Mitchell, call sign ‘Maverick.’ The only pilot ever to do an inverted negative dive in a MiG-28. He was also responsible for the most successful recruitment campaign in U.S. Naval history.

You see, after the release of Top Gun, enlistments in the Navy rose 500%. Their official campaign: Navy. It’s not just a job, it’s an adventure, which had run for the previous ten years, suddenly looked a little flat. It simply promised adventure. While Top Gun delivered it. Aerial tussles, homoerotic games of volleyball and a foxy astrophysicist. All wrapped up in Kenny Loggins’ Highway to the Danger Zone.

It was a bona fide smash. And as it turned out, a milestone in advertising innovation. A new brand platform to tell a more interesting story. Albeit as a by-product of a Hollywood movie. Which of course is why it worked so well. The audience was being advertised to without them even knowing.

We can learn a lot from Maverick Advertising. It represents what dedicated advertising always strives for but rarely achieves—getting into culture. It teaches us that we’re in the business of solving communications problems, not making ads. That we can look beyond traditional channels to tell our stories. And help brands succeed by talking to people in a different way.

Ellis from Die Hard and the art of negotiating

Rest in peace, babe

As a Nakatomi exec in Los Angeles, Harry Ellis was no stranger to high-stakes negotiations.

But he went completely off-book when he unsuccessfully tried to mediate between Hans Gruber and John McClane for the return of some explosives detonators.

His flawed negotiating strategy would end up costing him his life. Let’s look at the lessons to be learned from this sleazy drug addict to help you avoid professional humiliation (and or death) in your bid to become a negotiating powerhouse.

First off, never underestimate the other party. Also, as a sidebar, don’t negotiate on drugs. Ellis snorted a substantial amount of cocaine prior to his discussions with Gruber, which probably fuelled the misplaced confidence about his ability to deliver.

[To Holly McClane] “Hey babe, I negotiate million dollar deals for breakfast, I think I can handle this Eurotrash”

[To Hans] “It’s not what I want, it’s what I can give you”

Confidence is good but cockiness is a dangerous trait in a negotiator. Ellis was cocky in believing he could talk McClane down. Don’t prematurely promise what you may not be able to deliver, especially when you’re not yet privy to all the particulars of the situation.

[To Hans] “Maybe you’re pissed off at the camel jockeys, maybe it’s the Heebs, Northern Ireland, it’s none of my business”

Do your due diligence. Ellis had no idea about Gruber’s motivations or what he really wanted. He was ill-informed and reckless, two sure fire ways to lose any negotiation.

[To Hans] “Business is business. You use a gun, I use a fountain pen, what’s the difference?”

Good negotiators are astute. They can always distinguish between terrorism and

white collar crime. Mostly, negotiating is about common sense and street smarts.

“Hans, BUBBY, I’m your white knight”

Again with the over-promising. This high risk strategy leaves space only for the one most desired outcome. Negotiating is about managing expectations.

[To McClane] “I know you think you’re doing your job John and I can appreciate that but you’re just dragging this thing out”

Don’t patronise the person you are trying to persuade. And by the way, best to have everyone in the same room. Trying to thrash an issue out remotely adds an unnecessary layer of complexity to proceedings.

[To McClane] “I told them we were old friends and you were my guest at the party”

This wasn’t true. There is no place for dishonesty in negotiating, you will be found out and you will lose face. No doubt Ellis bullshitted his clients daily, but with his lack of knowledge and insight on the detonator issue, he misjudged the consequences of being caught in a lie.

[To McClane] “They want the detonators or they’re going to kill me”

So dramatic. Ultimatums rarely work. You catch more bees with honey than with vinegar.

[As McClane listens remotely] “What am I a method actor? Hans, babe, put away the gun this is radio not television”

Ellis was speaking like he was in control here. His lack of self awareness about the gravity of his predicament was staggering. There’s a saying in poker that goes something like—if you look around the table and you can’t spot the sucker, you’re the sucker.

Ellis, the poor naive deluded sucker. One’s ability to accurately assess the state of play in a negotiation cannot be overstated.

Somewhat surprisingly, Ellis never played his strongest card—giving up Holly McClane. Bad negotiating, but good constitution, I guess. All in all, Ellis’s attempt to broker a deal for the return of the detonators was pitiful. He underestimated both Gruber and McClane while grossly overestimating himself. Hardly surprising he got a bullet between the eyes.

Watch Ellis nearly ruin Die Hard here.